Main Street Macro: Some pain, more gain. Powell’s warning, a year later

August 21, 2023

|

The Federal Reserve holds its annual conference in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, this week. The high-profile symposium draws some 120 central bankers, financial executives, politicians, and academics, who meet to discuss important long-term economic policy issues.

The highlight of the event is a Friday morning speech given by Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell. Last year, Powell used his speech to deliver a warning for the economy: There will be pain.

At the time, inflation was soaring. Powell said that the trade-off for bringing inflation down would be felt on Main Street in the form of higher interest rates, potential job loss, and slower economic growth.

A year later, there’s good news on inflation, and we’ve escaped the worst of the pain that Powell warned of – so far.

Inflation has slowed – with one big exception

A year ago, the year-over-year change in the Consumer Price Index stood at 8.5 percent. Last month, it had fallen to 3.2 percent. That’s shy of the Fed’s 2 percent target but a far cry from the dangerously high levels we were experiencing a year ago.

But focusing on just the topline Consumer Price Index, a broad measure of the overall cost of consumer goods and services, makes the Fed’s fight against inflation look easier than it is. In practice, the Fed ignores volatile food and energy prices to focus on what’s known as core inflation.

By this measure, inflation is up 4.7 percent from a year ago, much higher than the Fed (or we consumers) would like.

And despite the relative ease with which price increases tied to food, energy, and goods have been calmed, price growth is proving harder to tame in services, particularly housing, which accounted for 70 percent of last month’s inflation growth.

As I’ve said before, housing is the must-watch indicator of the summer, a barometer of how rising interest rates are affecting the economy. The housing market also is a consistently accurate recession indicator, and right now is sending a clear warning.

The number of homes for sale in June was down nearly 14 percent from a year ago, according to the National Association of Realtors, and the median sale price hit its second-highest level on record, reaching $410,000, just $3,600 shy of the record-breaking price reached last year.

The national residential inventory shortage is pushing home prices up at the same time mortgages are getting more expensive. That means inflation in housing is actually getting worse, which could have serious long-term implications for the economy.

The labor market continues to be robust

In his 2022 Jackson Hole speech, Powell suggested that the Fed’s aggressive rate-hiking strategy would lead to job losses. That didn’t happen.

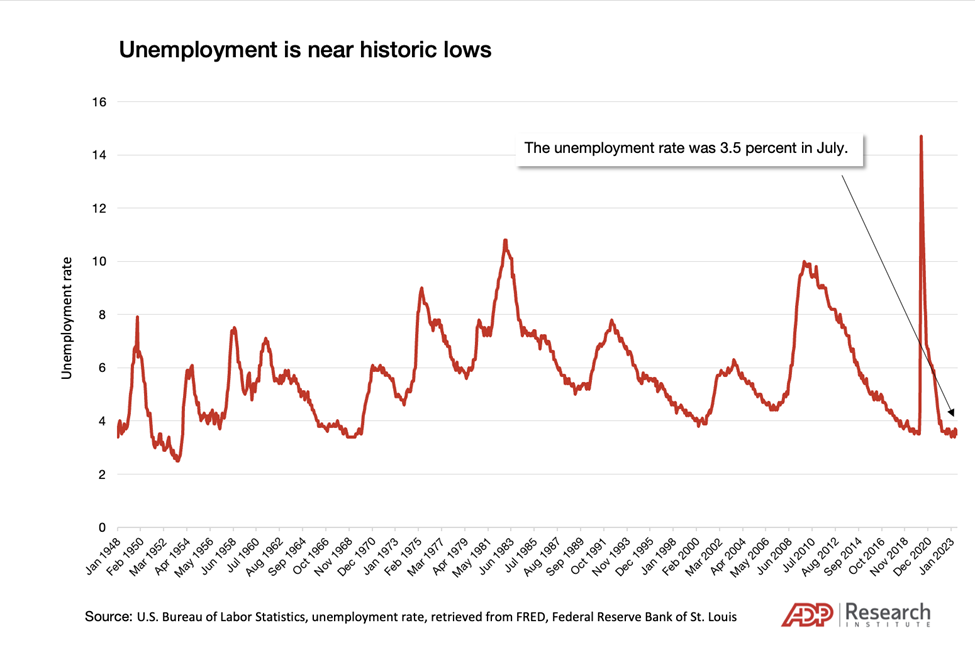

The unemployment rate was 3.5 percent in July, not far from a 54-year low matched earlier this year. Layoffs, too, remain low, with jobless claims dipping again last week.

Labor-force participation for prime age workers is higher than it was before the pandemic, a sign that labor market tightness, which the Fed worried would push up inflation, is loosening.

People are still spending

While the slowdown in inflation is good news, it obscures the hard truth that when prices go up, they often don’t come back down.

July retail sales suggested that consumers remain largely unflappable in the face of higher prices, as they continued spending at a rate that defied most economist projections.

Retail spending was up 0.7 percent from June, and up 3 percent from a year earlier. Real wages are up, too, and with a buffer of savings and solid job gains, consumers so far show little sign of any pain from higher interest rates.

The caution here is that the savings buffer built up by federal pandemic payments to households is falling fast. And after a three-year hiatus, student loan repayments will begin again this fall. The real pain could be yet to come.

My Take

To contain inflation, the Fed has pushed benchmark interest rates to their highest level in two decades, and the central bank probably isn’t done yet.

Based on its behavior, Main Street so far seems unscathed. But the pain of higher borrowing costs might start to sting small businesses, homebuyers, and consumers soon, if it hasn’t already.

So far, though, the economy has escaped the biggest pain of all – recession.

Does that mean we’ll get a worry-free speech from Powell this week? Unlikely.

Yes, the Fed has been able to navigate, by and large, its dual mandate of price stability and full employment. So far. To reach its 2 percent inflation target, the central bank might have to tighten the screws even more, pushing interest rates higher and keeping them elevated longer.

After more than a decade of rock-bottom interest rates, Main Street will need to build some muscle to hold up an economy increasingly burdened by high borrowing costs.