MainStreet Macro: Inflation and Coffee: A Love Story

October 17, 2022

|

I love coffee.

It’s what I wake up for. I’d like to say that I spring out of bed to make breakfast for my sons, walk my dog Lavender, take an invigorating run, or even dig into economic data (my passion).

The truth is, I wake up for coffee.

As I assess events currently shaping the global economy, coffee has come up. Yes, it powers me through my workday, but coffee also is a window into the forces that are rocking our world.

Here are three ways coffee is feeling the effects of the global economy.

Coffee prices are soaring

Last week, we got a fresh read on inflation. The good news is that consumer inflation slowed. The bad news is only by a smidgen. Headline inflation clocked in at 8.2 percent year over year in September, down from 8.3 percent in August. Falling gas prices helped push that decrease.

But the cost of food, which along with energy is one of the most volatile components of the consumer spending basket, is still elevated. Food prices were up 0.8 percent in September from the previous month.

No grocery aisle has been spared – produce, meats, cereal, and baked goods all are up by 9 percent or more from a year ago.

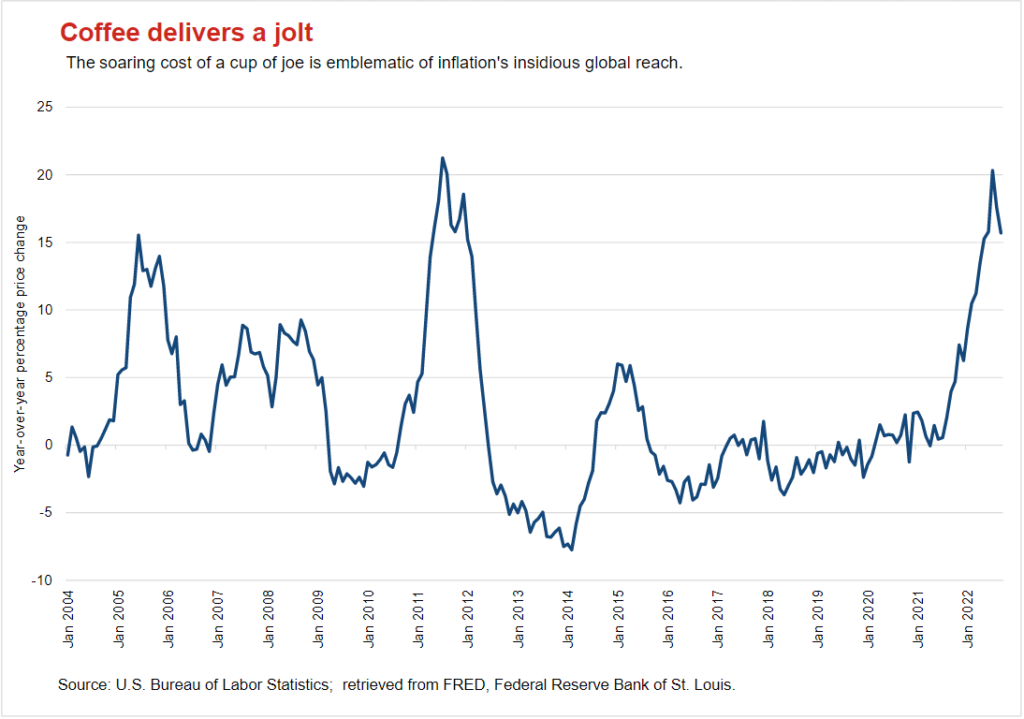

Which brings us back to coffee. Consumers are paying 15.7 percent more for their coffee than they did last year. In fact, year over year, the cost of a cup of joe has been rising by double digits every month since February.

That’s unusual. In the 4 years before the pandemic, coffee prices were flat to falling.

Fed policymakers don’t care about the price of coffee

Well, I don’t mean that literally. Central bankers are paying more for their caffeine just like the rest of us.

But generally, when Fed governors assess inflation, they tend to ignore the two components of consumer spending with the most dramatic monthly swings – food and energy.

Last week’s data showed that core inflation – the cost of goods and services minus food and energy –– accelerated in September, increasing 6.6 percent from a year ago compared to a 6.3 percent increase in August.

That’s three times the Fed’s target rate of inflation of 2 percent.

Supply chain shortages were the trigger for last year’s price increases. Today’s culprit is the service sector. Rents and mortgage payments, medical care and transportation are driving overall inflation higher.

Services-driven inflation has no easy solution. Consumers can easily switch their consumption from coffee to tea (even I can do that) and substitute other high-cost goods with little disruption. We can buy used cars – their prices have been edging down in recent months – instead of new cars, the cost of which were up 9.4 percent.

But housing costs are hard to avoid. Medical care is also a necessity. These services also are a big part of the consumer budget.

Remember, monetary policy works to reduce demand by increasing borrowing costs. But demand for housing, medical care and certain other critical services can’t easily be tamped down. What remains, then, is a rate-hike bitterness that’s hard for Main Street to swallow.

Coffee is multinational, just like inflation

Coffee’s journey from bean to cup is extremely complicated. It’s a commodity with a truly global supply chain. After it’s grown in Columbia, Vietnam, Ethiopia and other warm climates, it’s processed and shipped to retailers around the world.

Unfortunately, elevated inflation has a similar global footprint. With the exception of China and Saudi Arabia, it has affected all major countries worldwide according to the International Monetary Fund. In its annual report, the IMF last week warned that the global economy is heading for a sharper-than-expected slowdown due in large part to rising prices.

The IMF expects global growth to slow from 6 percent in 2021 to 3.2 percent this year and to 2.7 percent in 2023. Meanwhile, inflation is expected to stay elevated, reaching 8.8 percent for 2022 before slowing to a still-elevated 6.5 percent in 2023, then to 4.1 percent by 2024.

My Take

Not everyone will feel the effects of more expensive coffee, but most people will feel the pain of an expensive housing market, negative real wage growth, a slower economy, and higher-than-expected and persistent inflation. The Fed risks triggering a U.S. recession with its rate hikes. But the greater risk is an economy at the mercy of rising prices, which boost nominal growth while eating away at worker incomes and business revenues. We can only hope inflation eases quickly. But for now, that hope and a quarter – or 20 – will get you a cup of coffee.